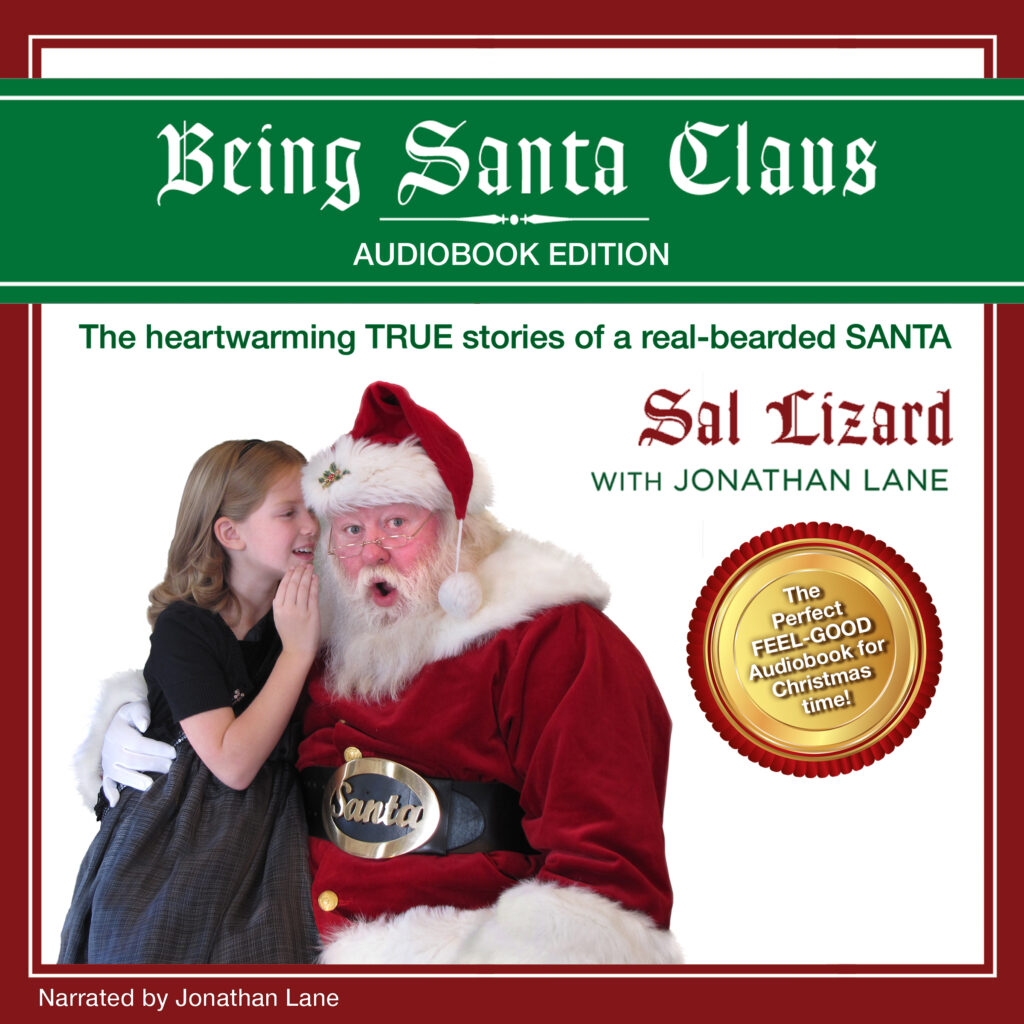

Being Santa Claus

NEW AUDIOBOOK & EXPANDED EDITIONS NOW AVAILABLE

WITH EVEN MORE SANTA SAL STORIES!

The History of Santa Claus and Christmas

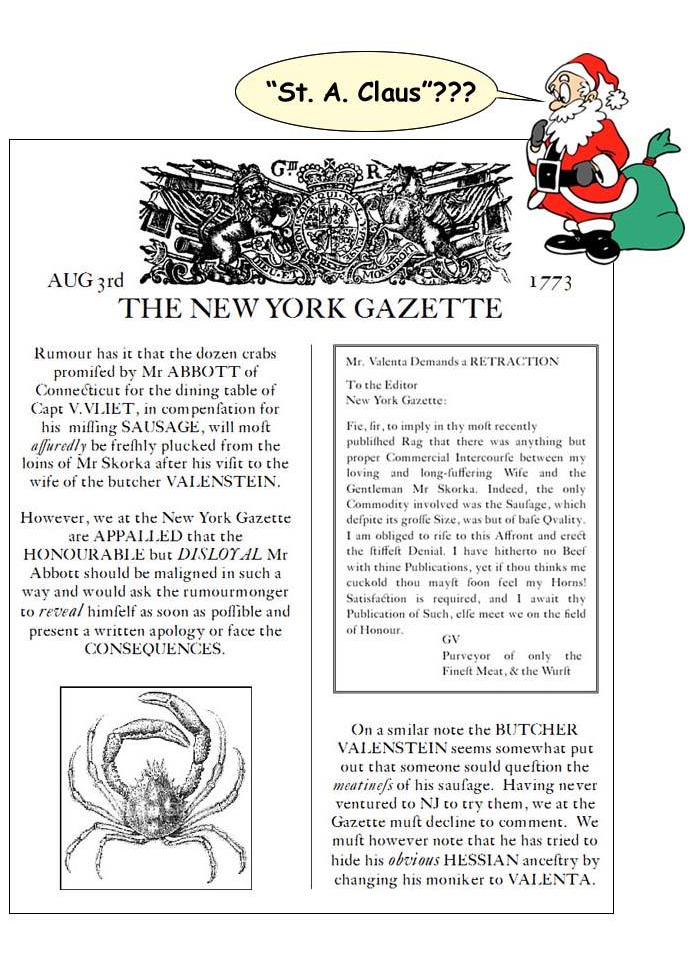

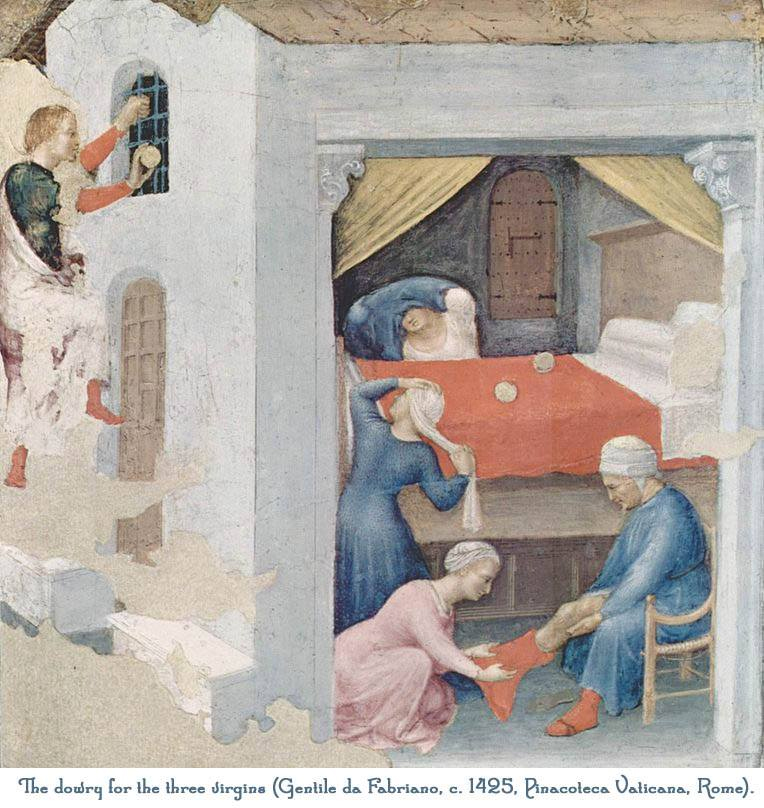

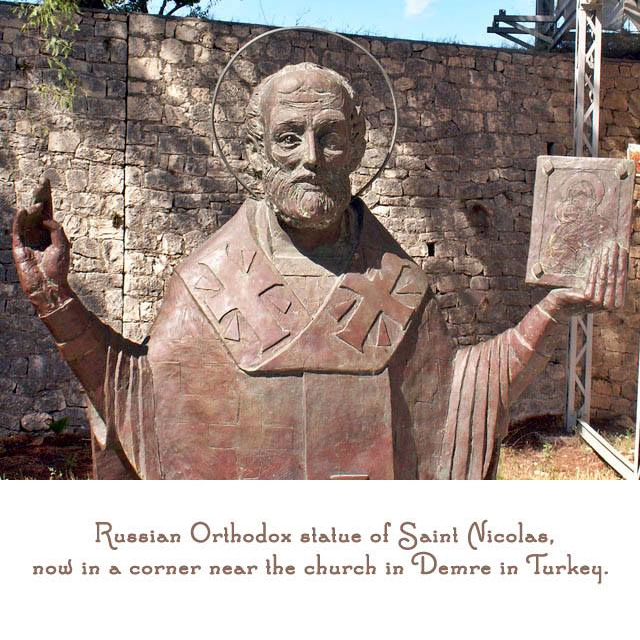

After the canonization of Saint Nicholas, December 6 (the day of his passing) became known as Saint Nicholas Day, a celebration of gift-giving throughout the Christian world. As the years and centuries went by, Saint Nicholas Day eventually merged with the Christmas holiday in many (but not all) European countries, since the two holidays occurred so close together. And that’s how Christmas became a time for giving presents and how Saint Nicholas got connected with a holiday celebrating the birth of Jesus Christ.

However, in parts of northern Europe, especially in some German-speaking areas, as well as in cities in the United States with German immigrant populations, Saint Nicholas Day remains its own separate holiday. In a number of places, children will leave letters for Saint Nicholas and/or carrots (or grass) for his donkey (or horse). The next morning, children find small presents, oranges, chocolate coins, and other treats under their pillows or in shoes or plates that they leave out, or in stockings that are hung. They also get candy canes, which are shaped like a bishop’s crozier. Interestingly, in Greece, the gift-giver is not Saint Nicholas but rather Saint Basil of Caesarea, and presents are handed out on New Year’s Day. The reason is that, in Greece, St. Nicholas is known as the protector of sailors and the patron saint of the Greek navy, military, and merchants. So the Greeks celebrate Saint Nicholas day with festivities aboard ships and boats both in port and out at sea.

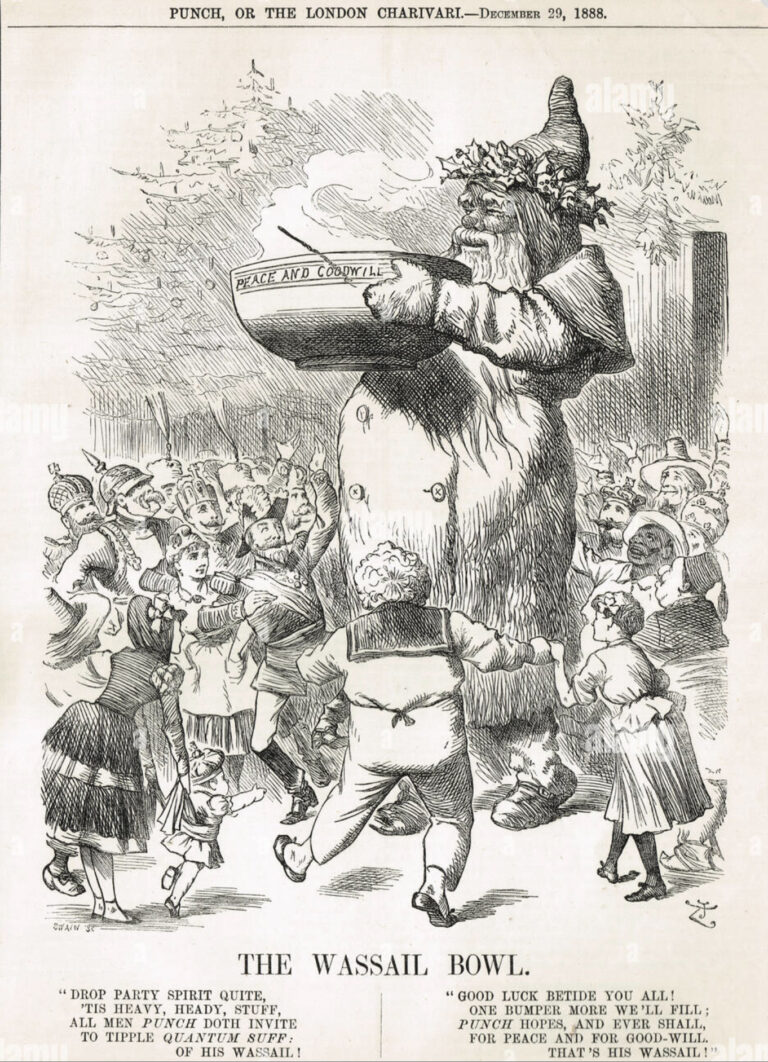

The Christmas carol starts: “Here we come a’ wassailing among the leaves so green…” But what the heck is a wassail? And why are the leaves green in the middle of winter? As it turns out, wassail is both a noun and a verb…and a greeting! The greeting came first, as the old Norse “Ves Heill” (which became the Anglo-Saxon “Waes Hael”) meant “Be in good health.” The proper response was “Drinc Hael” (“Drink in good health”). And this led to the noun wassail, which first appeared in written form in the old English epic poem “Beowulf” (written between 700 and 1000 A.D.) as the sweet, spiced mead or ale that was consumed…often in very liberal quantities!

What’s much more interesting, though, is how wassail became a verb. During the early middle ages throughout Europe, farmers would go out to their orchards during the winter months and pour cider and other alcohols onto the roots of their fruit trees in the hope that those trees would produce more fruit in the next harvest. This was known as wassailing and often included the singing of songs to frighten away evil spirits that might be living in the trees. As Christmas traditions spread throughout Europe later in the middle ages, wassailing began to be done on the twelfth night of Christmas, as farmers asked the baby Jesus to bless their trees. And that is how wassailing (the verb) came to be connected with Christmas and singing carols.

The origin of the Christmas tree

Although the Scandinavians brought trees into their homes for Juul, Christmas trees didn’t become a tradition in the rest of Europe until the 16th century. However, we have to go back 800 years earlier for the first-ever Christmas tree. One Christmas eve in the 8th century, Saint Boniface, a Catholic missionary to the Germans from Britain, chopped down a large oak tree that the Germans used for pagan worship. He told them the fir tree represented peace and eternal life and to gather around evergreen trees in the spirit of kindness and love, saying that the triangular shape of the evergreen represented the Holy Trinity. Devout Germans quickly embraced this idea, initially decorating their “paradise trees” with apples, nuts, berries, and white candles.

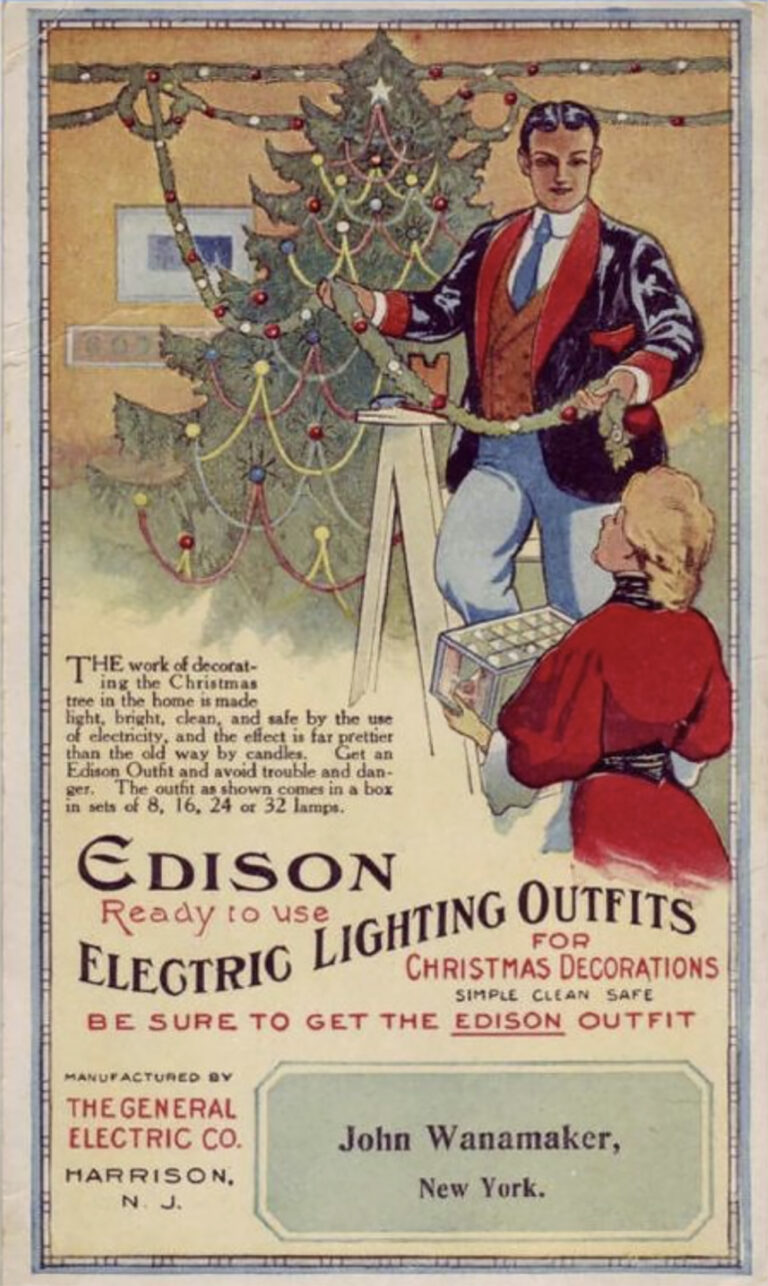

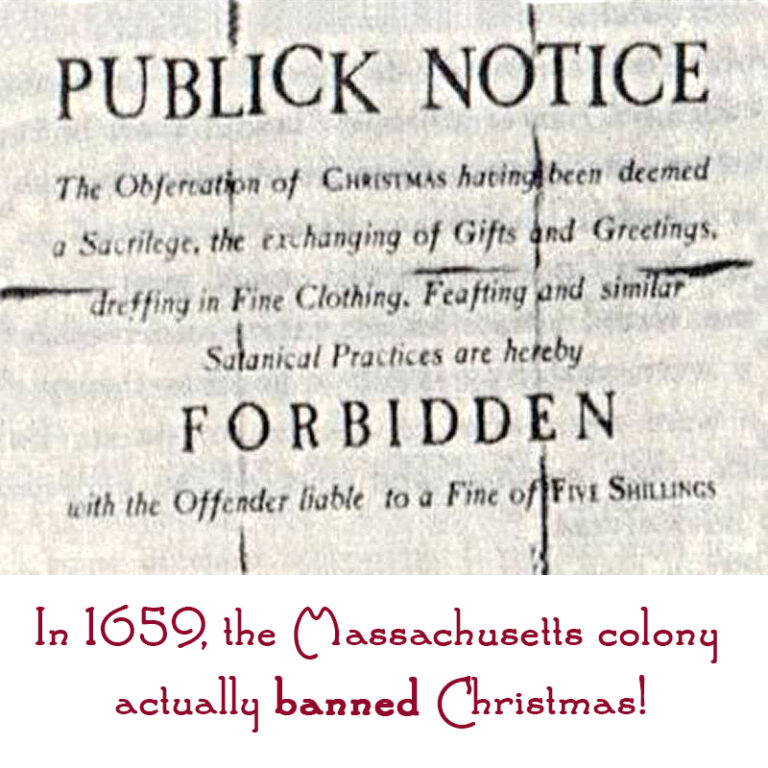

In the 15th century, more elaborate ornaments began to be incorporated onto the trees. In Latvia around 1600, roses were used to represent the Virgin Mary. In 1605 in Strasbourg, a tree was brought indoors for the first time in Germany and decorated with paper roses, wafers, candies, and candles. In 1610, tinsel made of pure silver was introduced. The tradition of taking trees inside the home and decorating them then began to quickly spread throughout Europe. Christmas trees took longer to catch on in America, however, as strict Puritanical groups initially saw the trees as pagan customs. Still, German settlers were more than happy to enjoy Christmas trees in the 1700s and 1800s until the rest of America caught on to all the fun!

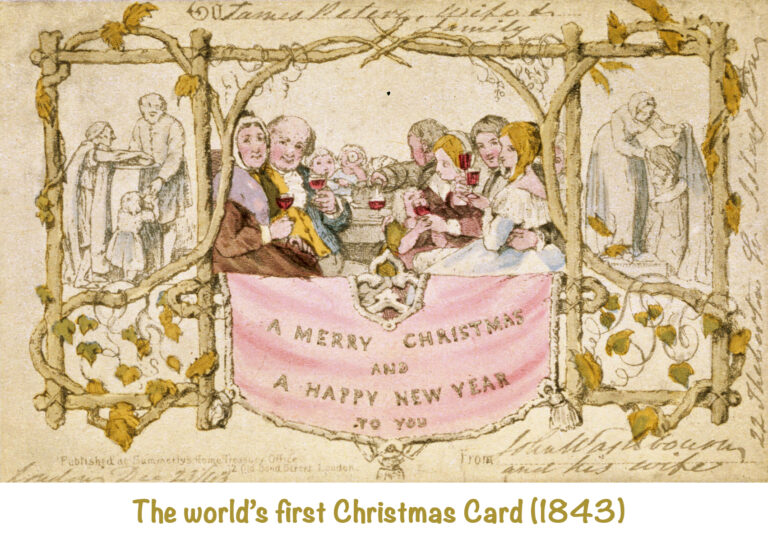

Cole had 1,000 of these printed and engraved at a size of what is now a typical post card, hand-colored (or coloured), and then sent half of them to his friends. The rest he sold for a shilling at the shop in London’s Old Bond Street. The steep price (a full day’s wages for many at the time!) and the fact that the cards showed someone else’s family resulted in lackluster sales of the remainder of the stock. It wouldn’t be until the advent of more affordable color printing a couple of decades later and the penny post allowing for cheap delivery of mail that Christmas cards began to catch on with those who weren’t among the wealthy elite.

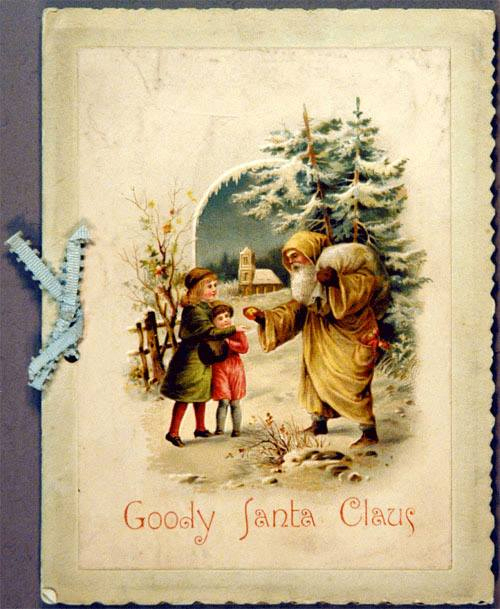

Santa, must I tease in vain, Deer? Let me go and hold the reindeer,

While you clamber down the chimneys. Don’t look savage as a Turk!

Why should you have all the glory of the joyous Christmas story,

And poor little Goody Santa Claus have nothing but the work?

It would be so very cozy, you and I, all round and rosy,

Looking like two loving snowballs in our fuzzy Arctic furs,

Tucked in warm and snug together, whisking through the winter weather

Where the tinkle of the sleigh-bells is the only sound that stirs.

You just sit here and grow chubby off the goodies in my cubby

From December to December, till your white beard sweeps your knees;

For you must allow, my Goodman, that you’re but a lazy woodman

And rely on me to foster all our fruitful Christmas trees.

While your Saintship waxes holy, year by year, and roly-poly,

Blessed by all the lads and lassies in the limits of the land,

While your toes at home you’re toasting, then poor Goody must go posting

Out to plant and prune and garner, where our fir-tree forests stand.

What’s the difference between Santa Claus and Father Christmas?